NormandyTours

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (November 20, 1874 – January 24, 1965) is one of the most iconic figures of not only World War II, but 20th century history. He is remembered for many things: his dogged opposition to Nazism; his rally of Britain after early setbacks, and his leadership of the country as Prime Minister during the war; his clashes with other wartime leaders while advancing his agenda; his contribution to the post-war world worder; his wit and memorable quips (many falsely attributed to him); his history books; and his impressive drinking habit (often exaggerated, according to some). He was a complex person who lived a complex life in complicated times. Our article, the first part of which is published almost on the 174th anniversary of Churchill’s birth, will take a brief look at his life, addressing both the acclaimed and the controversial about the man.

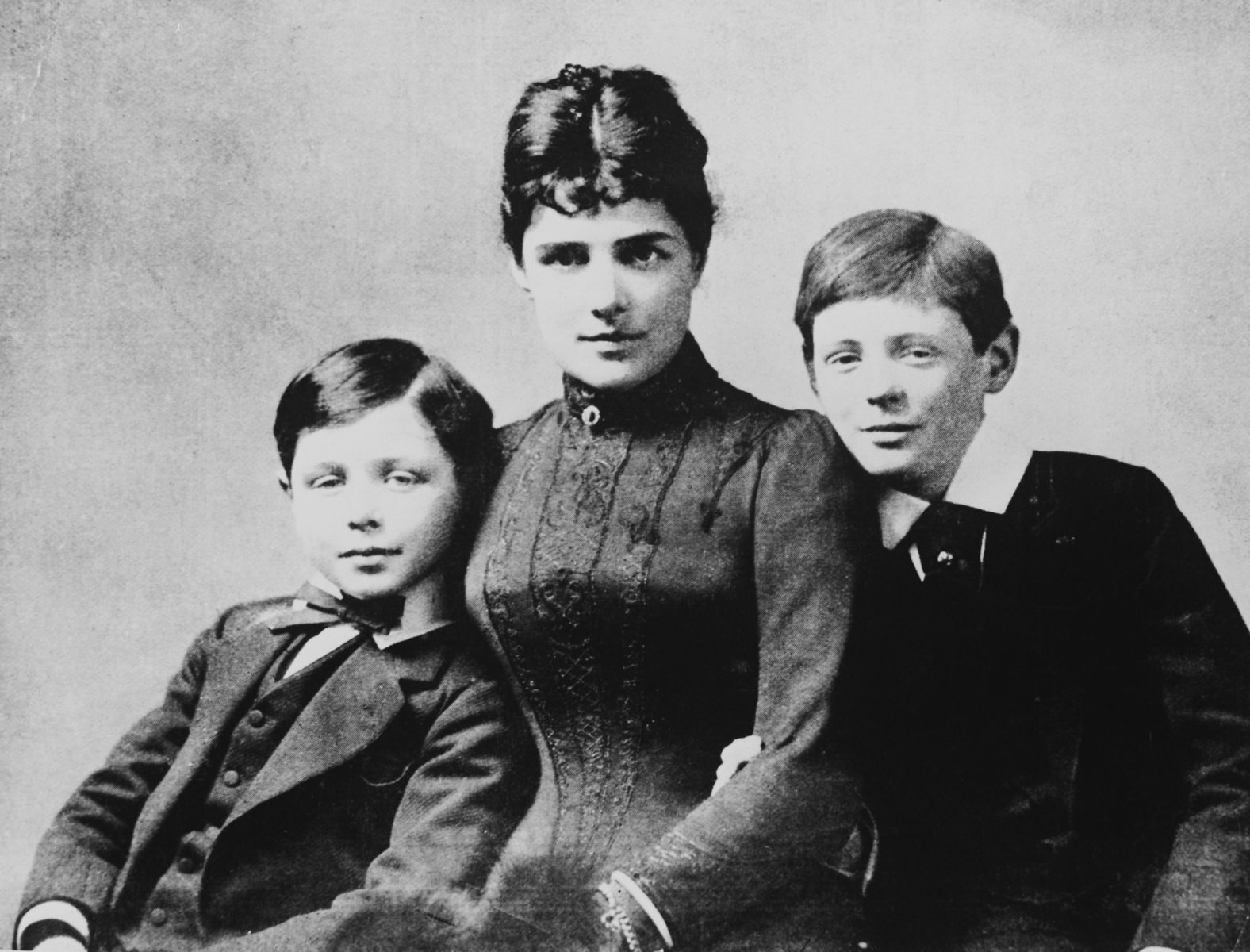

Churchill had mixed English-American heritage. His father was a British Conservative politician who died at the age of 46, giving Winston the belief that he too will die young. On the same side of the family, Winston also descended from John Churchill, the 1st Duke of Marlborough, a 17th century statesman who was one of the greatest military commanders of British history and the eponym of the Churchill tank. (The Tortoise in the Race) Winston’s mother was American and family lore holds she had partial Iroquois ancestry. The parents became effectively estranged while Winston and his brother Jack were still very young; both parents were distant, and Winston’s closest relationship was to his nanny.

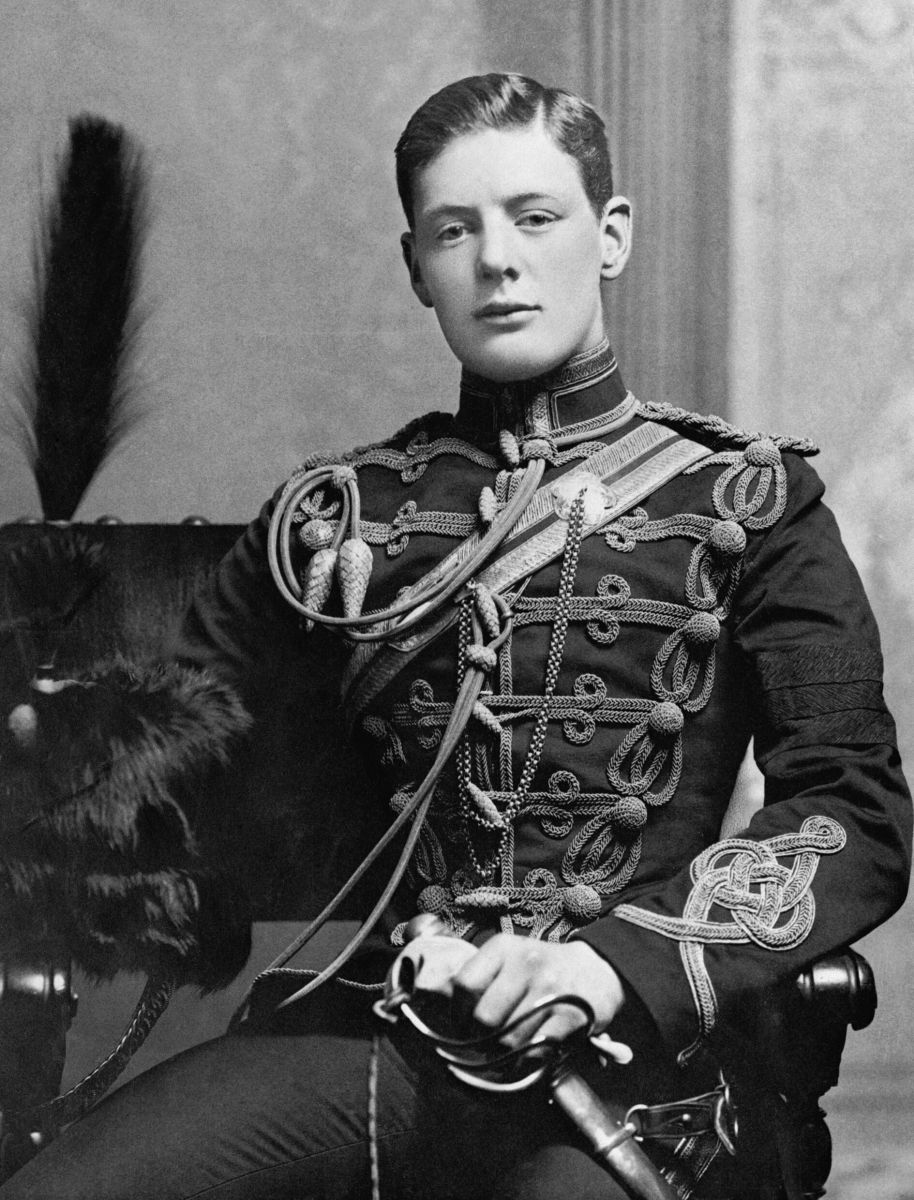

Churchill’s father wanted a military career for his son, so Winston’s last three years in school involved preparation for it. He was admitted to the Royal Military Academy on the third attempt, was accepted as a cavalry cadet, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in 1895. He probably never intended to stay in the military forever and only considered it as a steppingstone into politics.

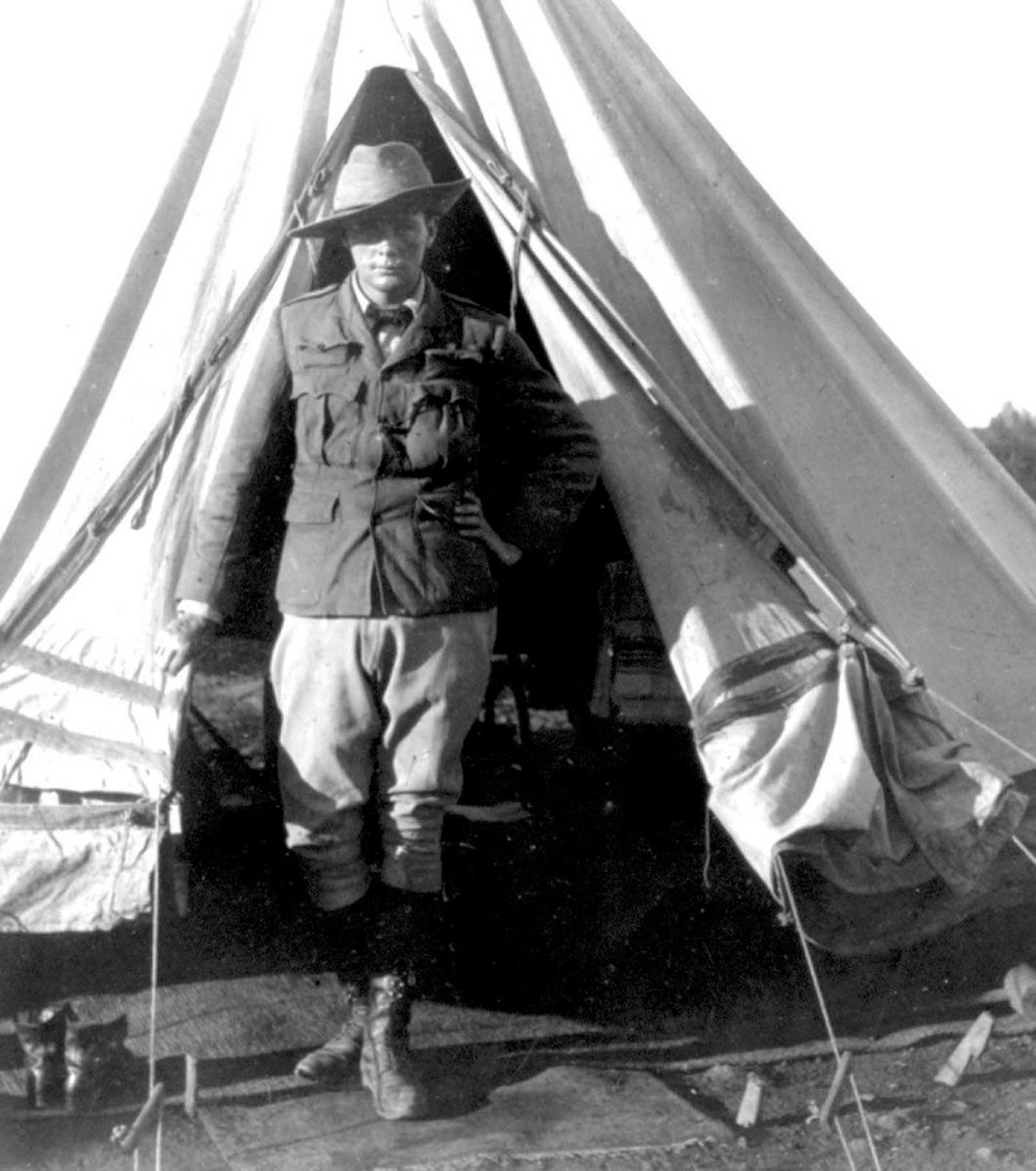

He was keen to see action and tried to get a war zone posting. He got it and was sent to Cuba to observe the Cuban War of Independence. He was also under orders to find out more about a new rifle the Spanish were using.

Churchill joined a Spanish fighting column and, according to his own account, first came under fire on his 21st birthday: a bullet ripped through his tent and another one hit an orderly standing outside when guerillas attacked the unit he was attached to.

A second lieutenant’s salary could not afford Churchill the lifestyle he felt was expected in the cavalry, so he broke military etiquette by writing reports to London papers to supplement his income, beginning a long career in journalism that lasted well into his political career.

Churchill’s unit was sent to India in 1896, and he joined numerous expeditions. It was during one such expedition that he was sent with 15 other soldiers to scout ahead. They ran into a hostile tribe on the way back and got into a firefight. They received reinforcements and continued on their way, only to be ambushed by another, much larger force. The enemy fire was so intense that the British and their Sikh reinforcements had to abandon a wounded officer whom Churchill witnessed being hacked to death. Despite the enemy’s superior numbers, Churchill only retreated after receiving a written order to do so, as he wanted to make sure he would not be tried for desertion. It took another two weeks of fighting to retrieve the body of the fallen officer.

Churchill also started to supplement his lacking academic education by reading books while in India. Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and British atheist philosopher Winwood Reade’s The Martyrdom of Man inculcated in him a strong anti-Christian sentiment, and he remained an agnostic even in later life.

Churchill joined an 1897 campaign against Pashtun rebels in northwest India. His book about the campaign launched his writing career; writing became Churchill’s way to cope with what he called his “black dog,” his recurring bouts of depression throughout his life.

Churchill accompanied the 1898 Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan, where he took part in one of the last cavalry charges of the British Army. He wrote a popular book about the events, but his African experiences ended his military career, at least for a while. Churchill saw how unmercifully the British were treating the enemy wounded; he also witnessed how Lord Kitchener, the leader of the expedition, ordered the destruction of the tomb of Muhammad Ahmad, a recently dead local leader who dealt a sore blow to British expansion a few years earlier. After the dome of the tomb was destroyed by gunboat fire, Ahmad’s body was disinterred, beheaded and thrown into the Nile, while Kitchener kept the head as a trophy and allegedly intended to use the skull as a drinking cup. These two incidents prompted Churchill to leave the army; he repeatedly spoke in favor of treating defeated enemies mercifully later in life.

It was time for Churchill to enter politics. The two main political parties in the U.K. at the time were the Conservatives and the Liberals; the Labour Party would appear in a few years and make rapid strides. Churchill’s father was a Conservative politician, but Churchill, full of reform ideas, once described himself as “a Liberal in all but name.” The one Liberal issue which was a dealbreaker for him was that of Irish home rule, the proposition that Ireland should be given some form of self-government while still staying inside the British Empire. Churchill could not bring himself to endorse the idea, and went with the Conservatives (in power at the time), running and narrowly losing in an 1899 by-election.

He traveled to South Africa later that year to report on the Second Boer War. Tension between Britain and the independent Boer republics was peaking due to the discovery of gold and the sudden influx of foreigners. Hostilities broke out in October, when Churchill was already in the country. Churchill was captured by the Boers and sent to a POW camp. He escaped in December and made it to Portuguese East Africa by stowing aboard freight trains and hiding in a mine, becoming a celebrity on his return home.

He briefly rejoined the army and participated in the relief of the town of Ladysmith from Boer siege, and the capture of Pretoria, being among the first British troops to enter both places. Despite having been captured by the Boers earlier, Churchill spoke up against anti-Boer prejudices and called for generosity and tolerance in dealing with the defeated Boers.

Back in Britain, Churchill stood for a seat once again, this time at the general elections, and won by a narrow margin, becoming a Member of Parliament (MP) at the age of 25. MPs were unpaid at the time, and Churchill had to go on a lecture tour in Britain, Canada and the U.S. to maintain the lifestyle he was accustomed to. In America he met Mark Twain, President William McKinley and former President Theodore Roosevelt (who took a great disliking to him for uncertain reasons).

Churchill took his seat in the House of Commons in 1901 and quickly got on the wrong side of most of his fellow Conservatives over several issues. He disagreed with increases in army funding and wanted a higher budget for the navy instead. He was also an advocate of free trade while the official Conservative line called for trade protectionism via import tariffs. He opposed a government-proposed bill to curb Jewish immigration, declaring he was in favor of "the old tolerant and generous practice of free entry and asylum to which this country has so long adhered and from which it has so greatly gained." Constantly drifting away from the Conservatives, he crossed the floor and joined the Liberals in May 1904. As a Liberal PM, Churchill became known as a radical, associating with fellow Liberal PM David Lloyd George, who would become the British Prime Minister during World War I.

Conservative Prime Minister Arthur James Balfour resigned in December 1905, and King Edward VII replaced him with Liberal leader Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Campbell-Bannerman called for a general election in January 1906 to secure a Liberal majority, which he got with a landslide. Churchill found himself on the government’s side again.

Churchill was given a junior ministerial position in the new government as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonial Office. His first task was to help draft a constitution for the Transvaal, and help oversee the formation of a government for the Orange River Colony, two South African regions conquered by Britain in the Second Boer War. Churchill sought to create equality between the British and the defeated Boers, and to gradually phase out the use of Chinese indentured labor in South Africa. He also voiced concern over the relations between European settlers and black Africans; he spoke up against the “disgusting butchery of the natives” by Europeans after a Zulu uprising was defeated.

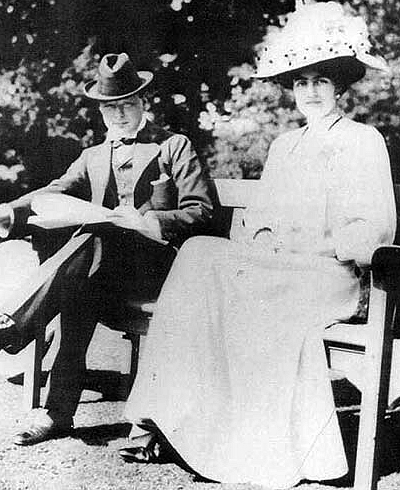

Prime Minister Campbell-Bannerman was terminally ill and was replaced by Herbert Henry Asquith in his position in 1908. 33-year-old Churchill was made President of the Board of Trade. He also married Clementine Hozier in the same year, and the couple had their first child in 1909 – their marriage would remain stable and happy.

Churchill stayed a reformer in his new position. He arbitrated an industrial dispute between ship-workers and their employers, and established a Standing Court of Arbitration to deal with similar disputes. He and Lloyd George promoted a “network of State intervention and regulation.” Building on Lloyd George’s work, he introduced a bill which limited miners to eight-hour workdays, and created Trade Boards to prosecute exploitative employers and establish the principle of minimum wage and the right to meal breaks. He proposed a bill to establish Labour Exchanges to help the unemployed find jobs, and a partially state-funded unemployment insurance scheme.

All of this was expensive, of course, and Churchill and Lloyd George called for a reduction of naval expansion, believing that war with Germany was avoidable. In April 1909, Lloyd George, as Chancellor, presented the “People’s Budget,” a budget proposal that called for unprecedented taxes on the rich to fund social welfare programs. Churchill was an ally in this, and some Conservatives took to calling the two the “Terrible Twins.” The proposal passed through the Commons but was vetoed by the House of Lords, whose members were the sort of people who stood to suffer a tax hike from it. It took a year of wrangling, including Churchill proposing the outright abolition of the House of Lords, until the Lords relented and the People’s Budget passed.

In 1910, Churchill was promoted to Home Secretary. He implemented prison reform, establishing educational innovations like prison libraries, requiring four stage entertainments for inmates each year, relaxing the rules on solitary confinement and proposing an abolition of automatic prison sentences for people who failed to pay fines. Most cases of imprisonment of minors were also abolished. He also supported further bills to protect the rights of coalminers and shop employees, and helped draft Britain’s first health and unemployment insurance legislation.

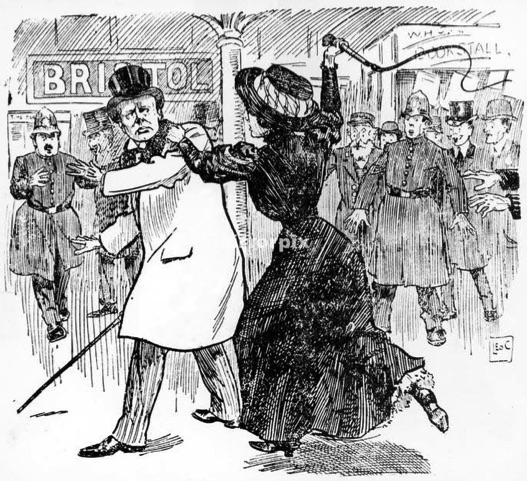

A major issue at the time was women’s suffrage. As a young man, Churchill was against it, believing (like most men and many women at the time) that women’s interests were already served through the votes of their male relatives. By 1910, Churchill grew to offer lukewarm support to suffrage, but only if a referendum proved that most (male) voters supported the idea. Such a referendum failed to manifest as the Prime Minister was against it.

Churchill’s earlier support for cutting military funding in favor of social reform ended with the Agadir Crisis of April 1911. Precipitated by French territorial expansion in Morocco, the faceoff between France and Germany showed that the European powers were sitting on a powder keg and a major war might break out at any time. Churchill reversed his former policy and started advocating for naval expansion.

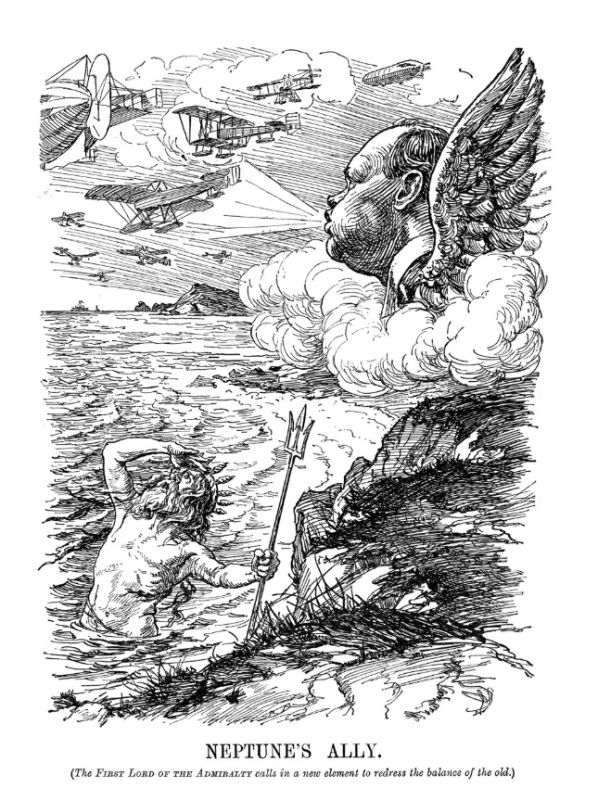

Churchill’s naval advocacy got him a new position in October 1911 as First Lord of the Admiralty, the political head of the Royal Navy. He spent two and a half years focusing on naval preparation, scrutinizing German naval developments and visiting every capital ship and naval base in the British Isles with his official Admiralty yacht. He supported a shift from coal- to more modern oil-powered engines, along with acquiring a 51% share in the profits of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company to make sure the navy will have enough fuel. (On the downside, the move away from coal ended up hurting the British coalmining industry, which lost a major customer.) Churchill also pushed for development of the Royal Naval Air Service, and has coined the word “seaplane.”

The government introduced the Home Rule Bill in 1912 with the intention of eventually giving Ireland a measure of independence. While Churchill opposed the notion in the past, he got behind the idea as he considered it better than the alternative of splitting Ireland into a larger part enjoying home rule and a smaller, Protestant part in Ulster still tied to Britain. He did not get his way in this matter, as Ireland was partitioned after the Irish War of Independence of 1919-21.

As First Lord, Churchill oversaw Britain’s naval effort in World War I, including the blockade of German ports, and submarine assistance to Russia. He also set up the Landship Committee to develop a weapon that could cross the deadly no man’s land between trench lines (Inside the World War I Trenches); the result was the tank.

Churchill’s other, far less successful involvement with the war was the disastrous Gallipoli Campaign. The idea was sound: by knocking the Ottoman Empire (allied with the Central Powers) out of the war, pressure on Russia would be relieved. Russia, in turn, could then increase pressure on Germany and Austria-Hungary on the Eastern Front, forcing them to send more troops there, thereby weakening the Western Front. Beating the Ottomans was supposed to be achieved by a coup de main: a fast attack up the Dardanelles Strait, landing troops right outside Istanbul. The campaign was too complex to discuss here, but the short version is that the surprise attack bogged down, started involving troop landings and deadly trench warfare, leading to a one-year debacle and horrendous casualties.

Churchill bore the brunt of the blame for the fiasco and was removed from his position. Resigning from the government (but keeping his seat as MP), Churchill returned to active service in the army and led troops at the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel on the Western Front. His unit saw no German offensive, but faced continuous shelling; Churchill once narrowly avoided death when a piece of shrapnel landed right between him and his cousin whom he was talking to. He left active service in the first half of 1916 and returned to the House of Commons, where he demanded greater recognition of soldiers’ bravery, the introduction of steel helmets, and the extension of the draft to include the Irish.

Churchill’s fortunes took a turn for the better again in October 1916: Asquith resigned as Prime Minister and was succeeded by Churchill’s old ally Lloyd George, who appointed him Minister of Munitions, and, after the armistice, both Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air. Churchill called for more domestic reforms and the establishment of the League of Nations to prevent future wars; he was also one of the few government figures who opposed harsh measures against defeated Germany. This latter was not only out of humanitarian considerations. Churchill considered the rise of communism in Russia as the greatest threat to Europe, and wanted to use the Germany as a bulwark against the Soviets.

The second part of our article will continue with Churchill’s career after World War I soon.

You can learn more about Winston Churchill, the Battle of Britain, the American build-up in the U.K. before the Normandy landings, and other aspects of the island nation’s struggle against Nazism on our Britain at War Tour.